When a blockchain boasts 400ms block times and sub-second finality across thousands of validators, the network propagation layer becomes critical infrastructure. Solana's Turbine protocol solves one of distributed systems' hardest problems: how do you broadcast gigabytes of block data to 3,000+ validators fast enough to maintain consensus without network congestion becoming the bottleneck?

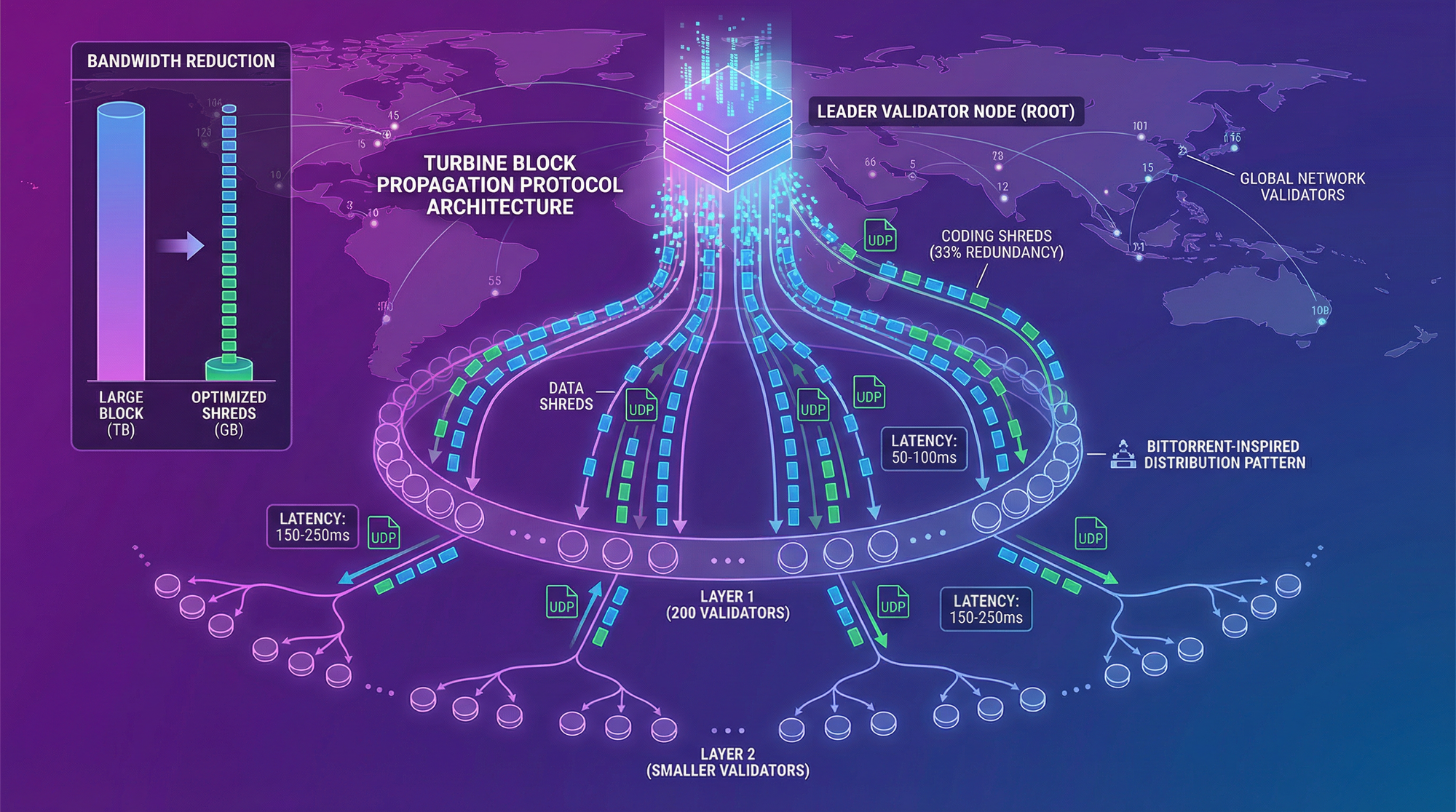

Traditional blockchains use simple gossip protocols where each node broadcasts to all peers—an approach that scales poorly and creates O(n²) bandwidth requirements. Turbine takes inspiration from BitTorrent to create a block propagation system that achieves logarithmic scaling while maintaining the security properties necessary for consensus.

The Bandwidth Problem in Distributed Consensus

Solana's throughput means the leader node must distribute massive amounts of data every slot. At 50,000 transactions per second with 400ms slots, each block contains roughly 20,000 transactions. If each transaction averages 200 bytes, that's 4MB of data that must reach every validator in the network within milliseconds.

With a naive gossip protocol, the leader would need to send 4MB to each of 3,000 validators directly, requiring 12TB of upstream bandwidth per second (4MB × 3,000 validators × 2.5 slots/second). No single node possesses that bandwidth capacity, and even if they did, network latency would make sub-second finality impossible.

Turbine reduces this O(n) bandwidth requirement to O(log n) by organizing validators into a tree structure and breaking blocks into erasure-coded packets that get distributed across multiple hops.

How Turbine Works: Block Sharding Meets Tree Propagation

Turbine's architecture involves several clever design choices that work together:

1. Packet Shredding

The leader breaks each block into small packets called "shreds" (typically 1280 bytes to fit in UDP packets). A 4MB block becomes approximately 3,200 shreds. This shredding serves multiple purposes: it enables parallel transmission, allows recovery from packet loss, and distributes the bandwidth load across the network.

2. Erasure Coding for Redundancy

Turbine applies Reed-Solomon erasure coding to the shreds. If you have 3,200 data shreds, Turbine generates additional coding shreds (typically 33% more, so around 1,056 coding shreds). The powerful property: any validator can reconstruct the complete block from receiving just 3,200 out of the 4,256 total shreds—it doesn't matter which 3,200.

This redundancy is crucial for reliability—validators don't need to receive every packet, and the protocol tolerates significant packet loss without requiring retransmissions.

3. Neighborhood Tree Structure

Validators are organized into a layered tree with configurable fanout (typically 200). The leader sits at the root and transmits different subsets of shreds to its immediate children (Layer 1). Each Layer 1 validator then retransmits its received shreds to its own children in Layer 2, and so on.

Here's the magic: with 3,000 validators and fanout of 200, you only need 2 hops (200 Layer 1 nodes can each reach 15 Layer 2 children, covering 3,000 total). The leader only transmits to 200 validators directly, and those 200 handle the rest of the distribution.

4. Neighborhood Assignments

The tree structure is deterministically computed from the leader's public key and current slot number. Every validator can independently calculate which "neighborhood" they belong to and who their parent and children are for any given slot. This eliminates coordination overhead—no central directory service needed.

The leader also rotates which shreds go to which Layer 1 validators to ensure even distribution and prevent any single validator from becoming a bottleneck.

Bandwidth Math: From Terabytes to Gigabits

Let's see how Turbine transforms the bandwidth requirements:

Leader Node Bandwidth

Without Turbine: 12TB/second (4MB × 3,000 × 2.5 slots/sec)

With Turbine: With fanout 200, the leader sends 4,256 shreds divided among 200 Layer 1 validators. Each gets ~21 shreds (27KB). Total leader bandwidth: 200 × 27KB = 5.4MB per block, or 13.5MB/second. That's nearly 900,000x improvement.

Validator Bandwidth

Each Layer 1 validator receives ~27KB from the leader and retransmits to ~15 Layer 2 children (405KB outbound). Each Layer 2 validator receives ~27KB and doesn't retransmit (it's a leaf node). The total network bandwidth used is roughly 4MB × (1 + fanout) = 4MB × 201 ≈ 804MB per block, distributed across all validators.

This scales logarithmically: adding more validators requires minimal additional bandwidth since they can be added as deeper tree layers.

Security Considerations in Turbine

Turbine's tree structure introduces potential attack vectors that Solana addresses through multiple mechanisms:

Erasure Coding Prevents Censorship

A malicious Layer 1 validator can't prevent its children from reconstructing the block because they receive shreds from multiple paths through the tree. The 33% redundancy means up to 33% of Layer 1 validators can fail or act maliciously without preventing block reconstruction.

Randomized Tree Topology

The tree structure changes every slot based on the leader's identity. An attacker can't predict which position they'll occupy in future trees, making coordinated attacks across multiple malicious nodes difficult to execute.

Stake-Weighted Retransmission

Turbine can optionally weight the tree construction by validator stake, ensuring high-stake validators are closer to the root. This increases the economic cost of attacks since compromising high-stake validators is more expensive than controlling many low-stake nodes.

Real-World Performance: Milliseconds Across Continents

Turbine achieves impressive propagation speeds in practice:

Layer 1 validators receive their shreds within 50-100ms of the leader producing the block. Layer 2 validators (which comprise most of the network) receive sufficient shreds to reconstruct within 150-250ms. By comparison, Bitcoin block propagation can take several seconds, and Ethereum beacon chain blocks propagate in 1-2 seconds across similar validator counts.

This speed enables Solana's sub-second confirmation times. Once a supermajority of stake-weighted validators receive the block (typically 200-300ms), they can vote on it, enabling the cluster to finalize transactions rapidly.

Turbine Evolution: From Theory to Production

Turbine has evolved significantly since Solana's launch. Early implementations used QUIC (Quick UDP Internet Connections) for transport, which provides congestion control and connection management. Recent versions leverage UDP directly for lower latency, with custom congestion control tuned for Solana's specific traffic patterns.

The protocol also implements adaptive fanout that adjusts based on network conditions—increasing fanout during periods of high packet loss or decreasing it when bandwidth is constrained. This dynamic adjustment maintains reliability without manual tuning.

Implications for Builders

Understanding Turbine helps explain several Solana characteristics that affect application development:

Why Block Sizes Matter

Larger blocks mean more shreds to propagate, which extends propagation time. This creates an upper bound on throughput—even with infinite compute, network propagation becomes the bottleneck. Developers should design applications with transaction size efficiency in mind.

Geographic Distribution Impact

Validators geographically distant from the current leader experience slightly higher latency. Applications requiring absolute minimum latency can optimize RPC node selection based on current leader location, though this is rarely necessary given Turbine's speed.

Validator Hardware Requirements

Turbine's efficiency means validators don't need extreme bandwidth. A Layer 2 validator can participate with ~1Gbps connectivity. Layer 1 validators need more (5-10Gbps), but this is achievable in modern data centers and significantly lower than naive approaches would require.

The Bigger Picture: System Design Philosophy

Turbine exemplifies Solana's approach to blockchain architecture: identify the theoretical limits (Shannon's theorem for network capacity), then design protocols that approach those limits rather than accepting traditional blockchain compromises.

Where other blockchains treat network latency as an unavoidable constraint, Turbine treats it as an engineering problem with solutions from distributed systems research. The result: a blockchain that can scale to thousands of validators without sacrificing the sub-second confirmation times that make Solana viable for real-time applications.

Next time you submit a transaction on Solana and receive confirmation in 400ms, remember that hundreds of validators across the globe reconstructed that block from thousands of UDP packets flowing through a carefully orchestrated tree structure—all in less time than it takes to blink.